The Reserve Bank of India in its quarterly credit policy meet raised repo rates to 5.75% and reverse repo rates to 4.5%. Repo is what banks pay to borrow from the RBI and Reverse repo is what they get when they park excess funds at the RBI.

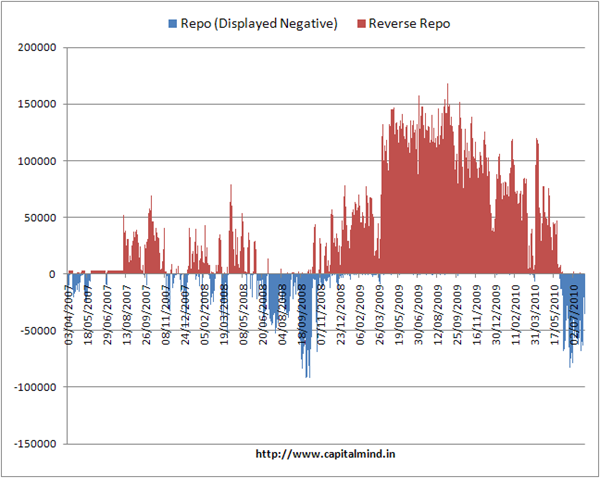

Over the last two years we have only seen money parked with the RBI, meaning the system was flush with money and banks weren’t quite lending. From May this year, after the 3G and BWA auctions, banks have started to borrow from the RBI instead, an order of 60,000 crores every day. (Repo means they have to place high quality securities with the RBI which they buy back – or “repurchase” – the next day or in a short period.)

The differential of 0.25% costs the entire banking system a miniscule 35 lakhs a day (0.25% of an average 50,000 crores) which is a sort of rounding error, but it’s not what they do anymore, it’s what they intend to do.

Here’s the repo/reverse repo graph over the last few years.

Will this increase retail interest rates? Even though liquidity is tight, bank margins are wide,so there is a cushion. But the interesting question is: at what point does the credit system break the back of inflation? RBI says it expects 6% inflation by year end.

And Tamal Bandhyopadhyay at the Mint got this one absolutely right. The “corridor” difference between the repo and reverse repo rates has shrunk, and there’s not much in reverse repo nowadays. And he says there’s a case for rates to go higher, because rates were at 9% in 2008 when inflation was at the 11% that May 2010 was revised to.

Many argue that the context of 2008 was very different; the economy was clearly growing above its potential and there were signs of overheating in certain pockets. A much higher policy rate was justifiable then, but not now, they say. This argument does not seem very convincing if one takes a close look at all macro-economic indicators. Growth in both exports and imports in the first half of 2008 and the first five months of 2010 is comparable. Industrial production growth in the first five months of 2010 is actually higher than in the first half of 2008. Bank credit growth was higher in 2008, but there is not much difference between growth in India’s gross domestic product, or GDP, between then and now. On average, the economy grew at about 8% in the first three quarters of 2008. The scene is not very different now. GDP growth was 8.6%, 6.5%and 8.6%, respectively, for the quarters ended September and December 2009 and March 2010. The Prime Minister’s economic advisory council has pegged growth for the current fiscal at 8.5%, higher than its February estimate of 8.2%. The International Monetary Fund’s forecast for India’s economic growth for 2010 is 9.4%.

It’s strange now. At a time when inflation’s gone through the roof, so to speak, we try to assuage ourselves saying that things will get better because, look at 2008. But oil prices were at $140 then, versus $80 today. Inflation fell because oil prices fell to $30, and alongside we did see corporate growth come down (but India’s growth didn’t fall too much, remember)

At this point, I don’t think it’s a supply issue that’s driving inflation. Supply problems would affect availability and literally everything, from fuel to CNG to tomatoes is available. If this is a demand problem – too much demand – then this piddly 0.25% is not going to help. In that case, I expect another policy rate increase as early as end August – bigger than 0.25%. Hold those floating rate plans.

Oh, and inflation indexes will change. The WPI will have a different series with the base year as 2004-05, but we don’t know from when. Food’s weight should go down, so inflation must moderate just looking at things that way.